Lily Clara Letter 7 - Hoodoos and Hoodlums

Bryce Amphitheater in Bryce Canyon National Park, 2011. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hoodoos and Hoodlums

Bryce Canyon: Stunning spires of crimson rock, reaching up to 200 feet high, light up each night under the setting sun along the southwestern edge of Utah. With thousands of these dramatic rock pinnacles, known as “hoodoos,” Bryce Canyon’s iconic landscape creates otherworldly views that have fascinated visitors for millennia.

Boasting the highest concentration of hoodoos found anywhere on Earth, Bryce Canyon is part of the Grand Staircase of sedimentary rock formations stretching from Utah to the Grand Canyon. But Bryce Canyon itself is not technically a canyon. This unique series of natural amphitheaters was carved into the red rocks of the majestic Paunsaugunt Plateau by centuries of ice erosion from above, rather than from a single canyon-creating stream. The resulting human-like formations earned the enigmatic area the name Unka-timpe-wa-wince-pock-ich, or “red rocks standing like men in a bowl-shaped ravine,” by the Paiute tribe who once dwelled among its cliffs. According to old Paiute legends, the hoodoos were once To-when-an-ung-wa (“Evil Legend People”) who were turned into stone by the all-powerful Coyote Spirit, resulting in the formations known as Anka-ku-wass-a-wits, which is Paiute for “red painted faces.”

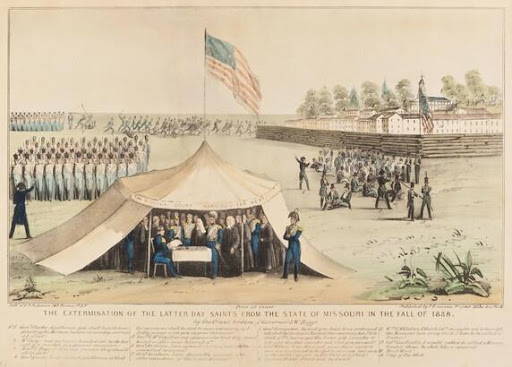

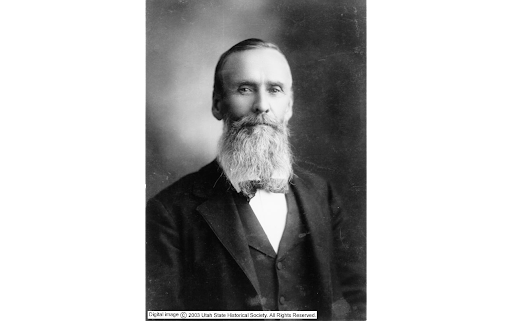

Bryce Canyon now attracts millions of visitors every year. But in 1870s and 1880s, its surreal but remote beauty was still largely unexplored and unknown. Bryce Canyon was originally inhabited by indigenous people from the Anasazi, Fremont, and Paiute tribes who first passed through the hoodoos at least 10,000 years ago. The area was later settled by Latter-day Saint pioneers in the 1850s, after they fled intense religious persecution in Missouri, where the Governor had even gone so far as to issue an “extermination order” authorizing the killing of anyone belonging to the new faith. The “Mormon” refugees first sought safety in Salt Lake City in 1847. As populations there swelled, the “peculiar people” began creating new settlements throughout the Southwest. Bryce Canyon was officially named after the area’s first Latter-day Saint homesteader, Ebenezer Bryce.

Bryce Canyon gained national recognition after the Union Pacific and Santa Fe railroads first published magazine articles in 1916 promoting its scenic wonders. Increased visitation from expanded railway service alarmed conservationists, who succeeded in designating Bryce Canyon as a national monument in 1923 and as a national park in 1928. Today, visitors travel from all over the world to hike among the hoodoos and marvel at the mysterious panorama.

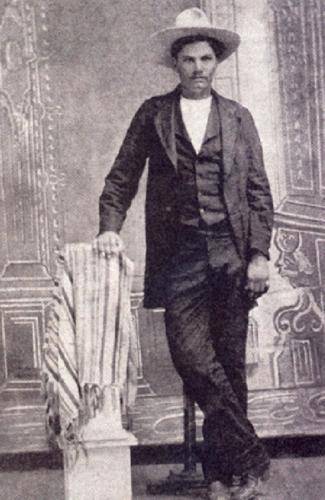

John Wesley Hardin: The notorious John “Wes” Wesley Hardin made history as the deadliest outlaw of the Wild West. After almost fatally stabbing a schoolmate at age 14 over an argument about a girl in their class, the next year in 1868 he killed a former slave and then killed three Union soldiers who were sent to arrest him. Thus began a killing spree that would be unrivaled for his time. Known for his quick temper and quicker draw of his guns, he later claimed to have killed 42 men by the age of 23 (although contemporary newspaper accounts only confirm at least 27 of those deaths could definitely be attributed to Hardin). He earned a reputation as a man “so mean, he once shot a man for snoring” too loudly, referring to an incident at the American House Hotel after an evening of drunken gambling.

Pursued by lawmen throughout Texas for almost nine years, he finally met his match with the Texas Rangers. This elite group of law enforcement was originally organized in 1823, and built a reputation for being able to handle the cases too difficult for local police forces. Not limited by city boundaries, Rangers’ duties spanned the state and were somewhere between an army and a police force. In 1877, Texas Rangers tracked Hardin down to Florida and confronted him on a train. Hardin apparently tried to draw his pistol, but it got caught in his suspenders. He was arrested, tried, and sentenced to 24 years in prison. While in prison, he wrote a wildly-embellished autobiography, studied law, and became superintendent of the prison Sunday School. After he was pardoned and released from prison in 1894, 17 years into his sentence, he passed the Texas bar examination and practiced law but still struggled to abide by the law. Hardin was killed just a year later after an argument with Constable John Selman Sr. Selman was later acquitted for the murder, with the jury apparently concluding that he had done the town a favor by bringing an end to the infamous gunman.

“Extermination of the Latter-day Saints from the State of Missouri,” lithograph print by H. R. Robinson, ca. 1840. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Portrait of Ebenezer Bryce, first pioneer settler and namesake of Bryce Canyon. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Studio photograph of John Wesley Hardin. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of John Wesley Hardin. Courtesy of Library of Congress.