Lily Clara Letter 4 - Railroads and Robberies

Wedding of the Rails

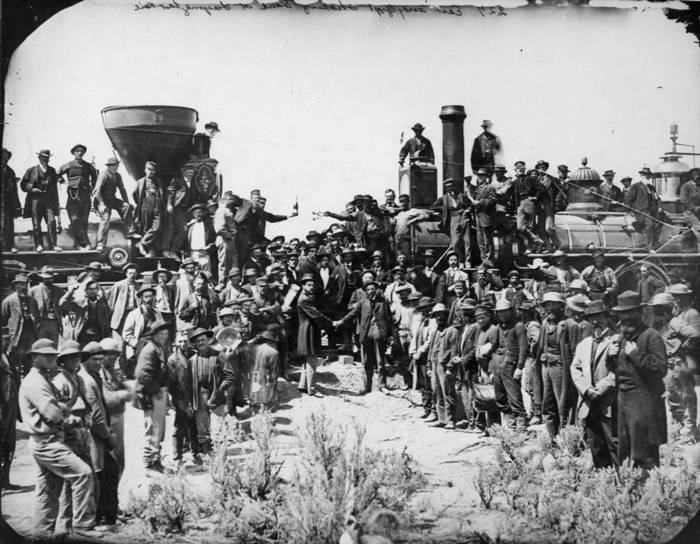

In the wake of the American Civil War, the completion of the first Transcontinental Railroad connected a fractured nation. When the final golden spike was ceremoniously driven at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, two railways become one and transformed life in the United States.

The resulting railroad, which connected the east and west coasts across 1900 miles of land, revolutionized the settlement of the West. Instead of an arduous 6-month wagon ride, travel across the continent could now be completed in about 1 week. Trains also expedited mail services, making it easier to stay connected with family and friends left behind. As large numbers of Americans headed west seeking opportunity and adventure, new towns and economies sprang up almost overnight along the railways. Mining towns like Frisco, where the population soared to over 6000 after the completion of the town’s railroad extension, owed much of their booming success to the Iron Horse.

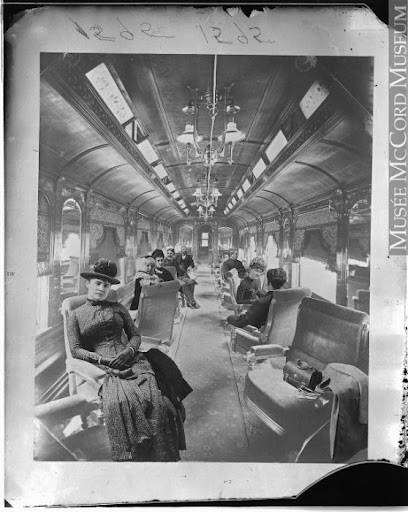

Railway construction hit its peak in the 1880s, at the height of the Gilded Age. Unparalleled speeds and improved passenger comforts like sleeping accommodations, diner cars, electric lights, and central steam heat made train travel increasingly popular in the final decades of the Nineteenth Century.

The most iconic image of the historic “Joining of the Rails” at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Railroad Depot, Glenn’s Ferry, Idaho, 1889. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Stick ‘Em Up

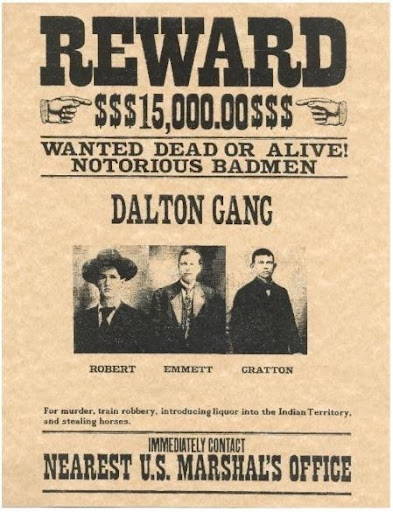

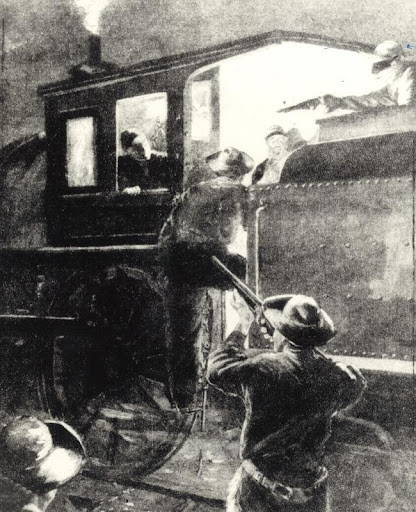

The expansion of railroads generally made travel across the continent faster, cheaper, and safer, but it was not without its own dangers. The first train robbery in the United States occurred before the Transcontinental Railroad was even completed. In 1865, more than a dozen outlaws held up a train in Ohio, robbed more than 100 passengers at gunpoint, and blew open safes containing thousands of dollars. They evaded the long arm of the law and sparked a new type of crime wave. The next year, the infamous Reno brothers boarded a passenger train in Indiana wearing masks and pointing pistols. They stole $13,000 from the safes on the train. For the next several decades, criminal gangs led by Butch Cassidy, Jesse James, the Daltons, and other outlaws made a lucrative business of train robbery. They live on as legends of the Wild West

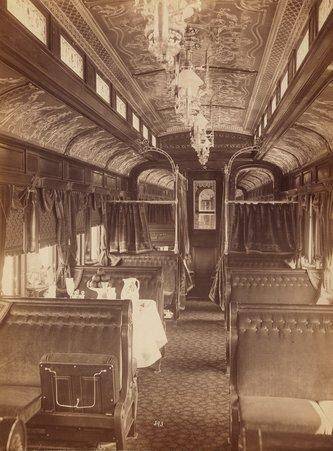

Dining car on a passenger train, ca. 1893. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum.

Victorian elegance of a drawing room car, 1886. Courtesy of McCord Museum.

The Bride and the Bandit

With limited rights, opportunities, and options, single women were particularly vulnerable in Victorian society. Lily Clara’s harrowing experience—confronting a train robber who turned out to be her own fiancé—is in fact based on the 1873 real-life tragedy of Eleanor Berry. Like Lily Clara, 22-year-old Eleanor took a chance on love and fate when she responded to a matrimonial advertisement. After 3 months of corresponding with Louis Dreibelbis, she enthusiastically accepted his proposal of marriage and boarded a Central Pacific Railroad train to join him in the mining camp near Grass Valley, California. On the last leg of her journey, the stagecoach was held up by masked, armed robbers who were gallant enough to acquiesce to her bold request to preserve her trunk of wedding clothes. But fortune was not in her favor. She met Louis for the first time at the altar, and within moments of saying “I do,” she recognized a distinctive scar on his hand and identified him as the leader of the gang of thieves. Unfortunately, Eleanor did not handle the shock as well as Lily Clara and was so distraught that she tried to take her own life. The intervention of family friends luckily saved her, but her experience demonstrates the great risks that many single nineteenth-century women were obligated to take to secure their place in society.

Wanted poster for Dalton Gang, “Notorious Badmen,” 1892.

Engraving of train robbery, Harper’s Weekly (January 16, 1892).