Lily Clara Letter 11 - The Cult of Mourning

Mourning ring presented to Ward Nicholas Boylston by John Quincy Adams upon the death of John Adams. It features a glass compartment for woven locks of hair surrounded by jet stones, ca. 1826. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Of all the fashions trending in the late Victorian Era, the explosive popularity of human hair jewelry was the most macabre. With high infant mortality rates, Civil War, and frequent outbreaks of disease, death was omnipresent. Victorian mourning jewelry provided comfort in the face of tragedy.

Queen Victoria herself was the biggest influencer when it came to mourning jewelry. The 1861 death of her beloved husband Prince Albert sent her into a deep depression and prolonged seclusion. She stayed shrouded in mourning clothes for the remaining forty years of her life and commissioned countless pieces of jewelry to remember Albert and other family members who passed away. This iconic leader made mourning jewelry fashionable and transformed it by using symbols of hope and love instead of the traditional skulls and reapers. Such symbols included cherubs, clouds, flowers, crosses, weeping willows, and anchors denoting unwavering faith. Small seed pearls were often used to represent tears.

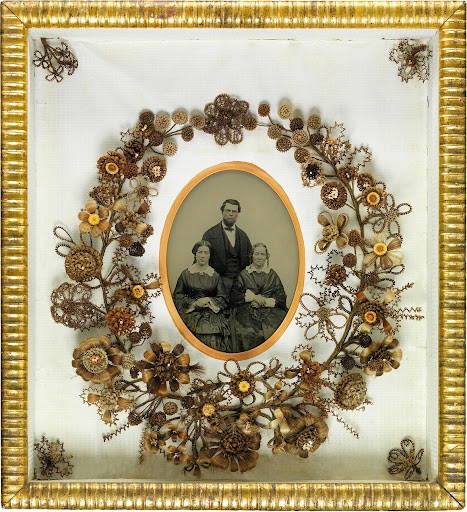

The art of hairwork was already a popular pastime in the 18th and 19th centuries and made a natural complement to the growing popularity of mourning pieces. Jewelry and other “memento mori” often featured hair from loved ones to memorialize sentimental expressions of loss and serve as tokens of remembrance. Since it does not decompose quickly, hair provided a particularly immortal quality to the relics and was believed to contain the essence of a person. The emergence of photography in the 1840s also led to the incorporation of photographs into mourning pieces.

Strict mourning etiquette of the time dictated that hairwork jewelry was permitted once the second stage of mourning began a year after the loved one’s death. While lockets containing photos or a lock of hair had been common for years, during the Victorian Era the hair itself became jewelry, with bracelets, rings, and necklaces themselves intricately woven from human hair. Mourning jewelry also typically featured jet or black onyx, although white materials such as ivory were used to memorialize children and unmarried women. With its widespread popularity, hairwork became increasingly intricate and elaborate for mourning jewelry as well as other types of remembrance art like mourning wreaths and shadow boxes. As new industrial forms of mass production increased access to such objects, it helped people at all levels of society cope with grief and loss.

1875 portrait of Queen Victoria, wearing several pieces of mourning jewelry which she popularized after the death of her husband Prince Albert. Courtesy of Royal Collection of the United Kingdom.

19th century brooch featuring a graveyard scene with willow trees made out of human hair from a departed loved one. Wikimedia Commons.

Learn the Lingo:

Frisco’s charcoal kilns: There were originally 36 charcoal kilns in Frisco, Utah, but only 5 of the beehive-shaped ovens have survived the test of time. The Frisco Mining and Smelting Company built them out of granite in 1877 to burn wood into coal in order to fuel the smelting process required to melt the silver and other metals at the Horn Silver Mine.

Victorian-era hair art often included intricate designs, such as this mid-19th century memorial hair wreath. Courtesy of College of Physicians of Philadelphia Mutter Museum.