Adelaide Magnolia Letter 17 - Letters, Gossip, and Satire

Letter #17 – Letters, Gossip, and Satire

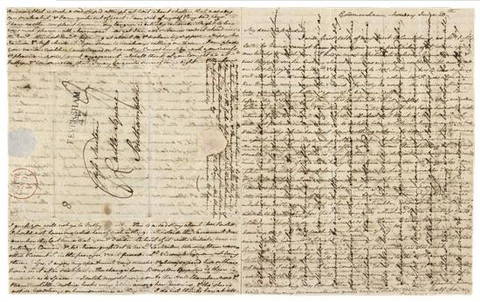

A Crossed Letter to Cassandra Austen from Jane Austen, 1808. Courtesy of the Morgan Library and Museum

Cross-writing, also known as cross-reading or cross-hatched lettering, was a very unique form of letter writing. The technique involves writing a letter, then turning the paper 90 degrees and writing another layer of text over the first. This allowed the writers to maximize use of limited writing materials, such as paper, and save on postage costs.

In a time when paper was a luxury item, individuals sought creative ways to make the most of their writing materials. One very well-known example of this is Jane Austen. Austen frequently used this method in her letters, especially to her sister Cassandra, as seen in the example above. This letter was written over the course of three days and includes inquiries into Cassandra’s strawberry gathering, how Jane is not enjoying Walter Scott’s Marmion, and a comment on the death of a “Mr. Waller” whom Jane doesn’t grieve over, and postulates that his widow doesn’t either.

This letter-writing technique was used widely until the price of paper became more reasonable. But for many the practice became habit and was a pattern in the way they communicated.

Satirical Caricatures of Gossip

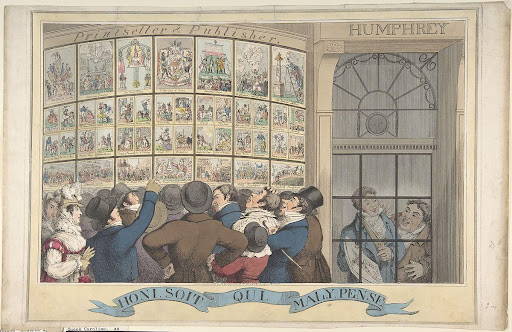

Honi Soi Qui Mal Y Pense: The Caricature Shop of G. Humphrey. Theodore Lane 1821. The Met

Gossip Column, Scandal Sheets, Society Column. There were many names given to the journalistic writing featuring a mix of factual information and juicy rumors about the members of the upper class in Regency England. These columns, usually found in newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, and even shop windows, covered a wide range of topics such as balls, fashionable trends, marriages, births, lavish parties, etc. But they would also contain the more scandalous affairs of political intrigue, personal feuds, and romantic entanglements.

Regency society columns were characterized by their witty and satirical tone, offering a mix of social commentary and gossip. Often these columns would be accompanied by caricatures depicting sardonic depictions of the topics. These caricatures became very common as photographs in newsprint were a thing of the future and added visual interest to the readers. While they often depicted social satire, political satire was a common theme in the caricatures of the era and could be created as prints and widely circulated to reach a broader audience.

As a vehicle for political and social propaganda, satirical caricatures became very important in shaping public opinion, challenging authority, and influencing political discourse. A very common subject of these drawings was The Prince Regent. The Regent, who was well known for his extravagant lifestyle and love for fashion, was often depicted as a corpulent figure, dressed in luxurious clothing and surrounded by fawning courtiers. These caricatures were set out to mock his excessive lifestyle and spending, his mistresses, and his lack in political acumen. As seen in the picture below, we see the Prince Regent depicted as a whale in the sea of politics being anchored as a prize by the Tory Party while the Whigs on the left are only left with the “liquor of oblivion.” Meanwhile, the Regent is ignoring all this and is eyeing a mermaid, depicting his current mistress, while ignoring her merman husband and the other mermaid depicting his former mistress.

The Prince of Whales or the Fisherman at Anchor. George Cruikshank 1812. The Met.

While the caricature is very amusing, there is also a very poignant commentary on how The Prince Regent was distracted by his pleasures seeming almost ambivalent to the politics around him. It is also a comment on his change in association from the Whig party to the Tory party, which angered and confused many. These caricatures were an important tool in spreading this discontent, and the Prince Regent never seemed to gain favor with his subjects.

George Cruikshank, unknown artist, 1836. National Portrait Gallery

One of the most prolific caricature artists of the time was George Cruikshank. Cruikshank, born in 1792, was the son of Isaac Cruikshank, who was also a well-known caricaturist in the late 18th century. George started his career as his father’s assistant and apprentice working in his print factory. George and his brother Robert helped their father with etchings, while their mother and sister colored in the finished prints. Between the ages of thirteen and eighteen George had already contributed to or completed 60 separate etchings.

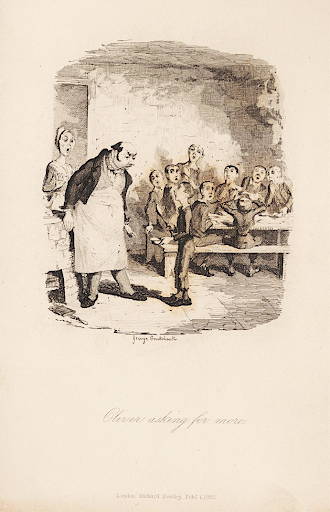

In 1811, at the age of 19, his father Isaac died, leaving George and Robert in charge of financially supporting their family. This is when George started to sell his political and social caricatures to publications, collaborate with others on political pamphlets and books, and eventually started to self-publish collections of his work. In his early thirties, George Cruikshank turned his talents to book illustration. He illustrated an estimated 850 books, but the one he is most well-known for is Oliver Twist. In fact, George illustrated many of Charles Dickens’ works, helping to increase Dicken’s popularity as well as his own.

Oliver Asking for More, George Cruikshank 1837. Yale Center for British Art

Sources:

https://janeaustenslondon.com/tag/regency-theatre/

https://reginajeffers.blog/2023/05/05/how-was-gossip-spread-so-easily-in-the-regency-era/

https://randombitsoffascination.com/2018/05/26/scandal-sheets-and-gossip-columns/

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/393176

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/24/books/jane-austen-prince-regent.html?smid=url-share

https://www.illustrationhistory.org/artists/george-cruikshank

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Cruikshank

https://brierhillgallery.com/george-cruikshank-1792-1878

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crossed_letter

https://rosenbach.org/blog/cross-writing-and-cross-reading/