Lily Clara Letter 5 - Boom to Bust

Ruins of Frisco’s charcoal kilns. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

Frisco, Utah: From Boom Town to Bust

The ruins of five beehive-shaped kilns dot a hill in the remote desert of Utah’s southeast edge. Along with crumbling foundations, abandoned buildings, and a dilapidated cemetery, these granite smelting ovens are now all that remain of a once booming town in Beaver County. In the 1880s, Frisco had the richest silver mine in the world and was one of the wildest towns in the West. Today, it is an almost-forgotten ghost town.

Frisco had a brief but eventful history. In 1875, two prospectors discovered a rich vein of silver, staked their claim, and established the Horn Silver Mine. They promptly sold it for $25,000, a profitable but short-sighted sale since the mine would eventually produce over $50 million in silver, zinc, copper, lead, and gold. The Frisco mining camp sprang up nearby, and by 1879 the United States Annual Mining Review and Stock Ledger dubbed the Horn Silver Mine “the richest silver mine in the world now being worked.” (1) After the Utah Southern Railroad completed an extension connecting Frisco to the rest of the nation the next year, production in the Horn Silver Mine skyrocketed and the population (800 people in 1880) soared to over 6,000 residents by 1885.

During its early years, Frisco also gained notoriety as one of the wildest towns in the West. With over twenty saloons, gambling dens, brothels, and widespread lawlessness, shootouts and murders were so common that the town reportedly had to hire a wagon to gather the bodies each morning for burial. The Frisco Cemetery was the biggest in the state at the time. Fed up, the law-abiding townspeople hired a new sheriff from Nevada in 1880. Sheriff Pearson was a quick draw and made it clear that no arrests would be made. He cleaned up the town by shooting any criminals on sight. His approach was so effective that he reportedly filled the makeshift “Boot Hill” criminal cemetery and restored order within six weeks. As the town regained safety and respectability, business boomed.

On February 12, 1885, the bustling town of Frisco was at its peak. Then suddenly, disaster struck. Just after midnight, the Horn Silver Mine completely caved in. Newspapers reported that “mammoth timbers were crushed into toothpicks, and a chunk of the earth’s crust more than 700 feet thick slide down between the walls of the mine.” (2) Witnesses claimed that the tremors from the massive collapse were felt over 10 miles away in away in Milford, where the force was strong enough to break windows, although it is more likely that both the mine collapse and the Milford tremors were caused by one of Utah’s occasional earthquakes. Fortunately, they were changing shifts at the time and none of the miners suffered serious injuries, but the town of Frisco was never the same.

Despite efforts to save the mine and regain its lost productivity, the once vibrant population dropped to 500 in 1900, and 150 by 1912. (3) The mine continued to produce ore, but the miners increasingly lived in nearby Milford. By the 1920s, Frisco was an abandoned ghost town. The crumbling kilns, which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, are now just shadows of the past.

(1) Encyclopedia of Immigration and Migration in the American West, vol. 1, Gordon Morris Bakken and Alexandra Kindell, eds. (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publishing, 2006).

(2) “The Horn Silver Cave,” Salt Lake Tribune (February 2, 1885).

(3) “Rise, Decline, and Renewed Promise of Frisco,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican (March 23, 1902).

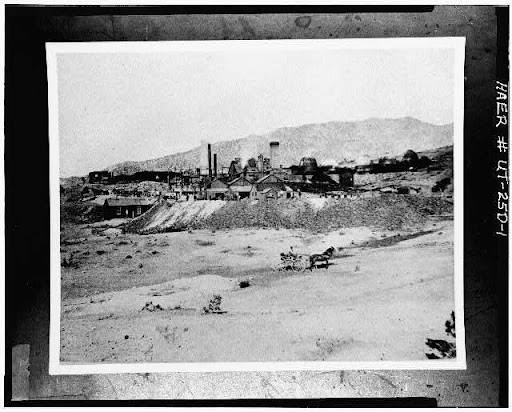

The Frisco Smelter in 1883, with kilns in the background. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

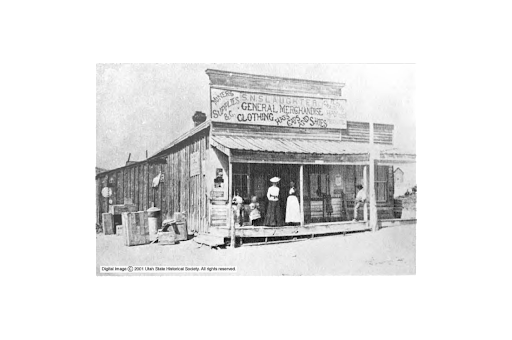

General merchandise and miner’s supply store in Frisco. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.