Lily Clara Letter 19 - Having a Ball

Rules and customs reigned supreme during the Victorian era, even when it came to entertainment. Hosting a Victorian ball was an elaborate affair, with even the most minute details dictated by strict social standards and extensive etiquette manuals, but they also offered occasional opportunities to break from convention.

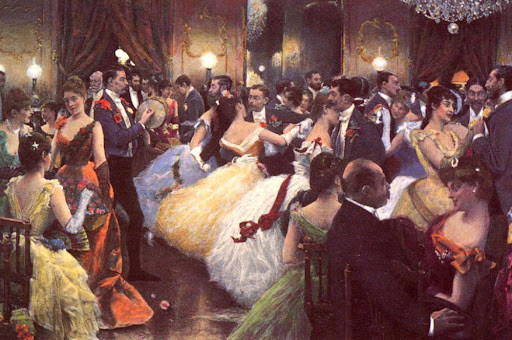

Often, a Committee of Arrangements was appointed to plan the ball, attend to the details, and ensure that it was all done properly. Rigid guidelines governed when invitations were sent, how the hosting venue was prepared, where to serve the elaborate food, the type of music, and the appropriate attire. Young ladies seeking an engagement were expected to wear light colored and lightweight gowns that were easier to dance in. Married women wore heavier fabrics, like silk, in light colors. Widowed women in mourning wore black, scarlett, or violet and would not participate in the dancing. Gloves were a necessity for all, including the men. Men also wore tailored dress coats and pants of the same color, with waistcoats, cravats, and white gloves. Each lady received a dance card, on which men would sign up for the privilege to accompany her in specific dances. Quadrille dances, involving four couples dancing in rectangular formation, were highly popular.

Countess of Warwick as Marie Antoinette at the famous Devonshire House Ball in 1897, which was held in London to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Photo by James Lafayette.

Balls were the defining fashion events of the Nineteenth Century. Debutante balls announced the entrance of a young woman into formal society and her eligibility for marriage. Signifying the importance of the ritual, debutante gowns were often far more elaborate than wedding gowns. Masquerade and costume balls were also particularly popular and invited guests to transform for the evening. Attendees dressing up according to a theme, often as specific historical or literary characters. Hidden behind masks and another persona, guests could briefly escape the strictures of polite Victorian society and engage in more brazen behavior.

Alva Erskine Smith Vanderbilt at her famous New York ball, 1883. Courtesy of Museum of the City of New York.

Balls also afforded hostesses an opportunity to establish themselves socially in the rigid hierarchy of the Victorian elite. Such was the case for socialite Alva Erskine Vanderbilt in 1883. The Vanderbilt name has now come to represent a type of American royalty, but that was not always the case. Considered “new money,” the Vanderbilts had been excluded from the upper echelons of New York’s social circles despite the family’s enormous wealth. After marrying into the Vanderbilt fortune, Alva decided to change their social standing by throwing the party of all parties. As excitement and press built around the upcoming event, one young New Yorker was glaringly omitted – the daughter of Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, leader of “The Four Hundred” list of New York’s Gilded Age high society. Astor had routinely snubbed and excluded the Vanderbilts, so Alva simply (and strategically) explained that because of the complex social customs, she was unable to invite the Astors because they had never formally called on the Vanderbilts. Mrs. Astor immediately made a formal visit, symbolically welcoming the Vanderbilts into “acceptable” society and securing a precious invite to the ball of the century. The Vanderbilt ball included nearly 1200 guests and cost approximately $250,000 (nearly $6 million today!). Its excess and opulence defined the era and transformed the upper crust of New York.

Extravagant fancy dress balls displayed Victorian high society at its best and were considered the pinnacle of aristocratic social life in Europe as well as the United States. Iconic scenes of swirling gowns and well-tailored dress coats continue to live on in the public’s fascination even today as a romanticized portrait of a bygone era.

“A Masquerade Ball,” ca. 1750 Lithograph by Firmin-Didot, Paris.